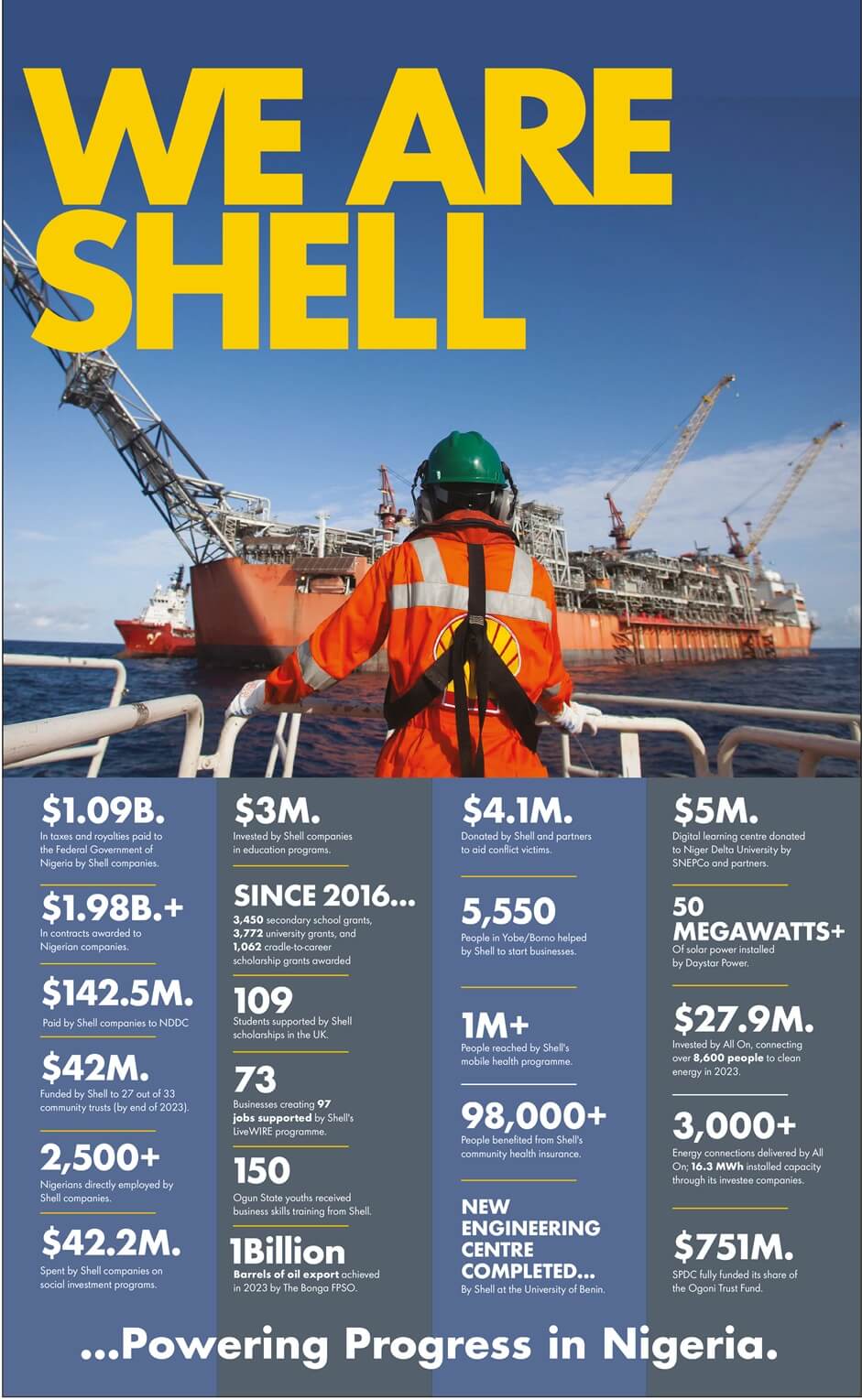

Students demonstrate against the position of the Spanish government to ban the self-determination referendum of Catalonia during a university students strike on Sept. 28, 2017, in Barcelona, Spain. (Photo: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

BARCELONA — Here in Spain’s second-largest city, famous for sun, sex, and sangria, it’s raining today, the mood is anxious, helicopters are overhead and flags are waving everywhere — the Spanish flag alongside the provincial flag of Catalonia, the northeastern province on the border with France, of which Barcelona is the capital. But by far the most numerous flags are the esteladas, the flag of the secessionist movement, signifying support for independence from Spain. They are being waved from rooftops, in front of City Hall, in marches down avenues, in pot-banging demonstrations through working-class barrios, and outside of schools — in 200 of which, locals are camped out, some with their children, occupying buildings for what they anticipate will be Sunday’s vote on independence for Catalonia. It’s a vote that the national government in Madrid declares illegal, and which the Constitutional Court suspended three weeks ago. Yet the regional government insists that it will take place anyway, in the face of 10,000 police from outside the region who have been sent in to prevent it by sealing off voting centers, shutting down Internet sites and apps, and seizing the Catalan telecommunications center.

These moves have prompted WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange to declare what’s happening here to be the “world’s first internet war.” Sentiment on the issue of secession has run fierce here for the past five years, but lately, suspected Russian mouthpieces Assange and Edward Snowden — as well as Russian media outlets RT and Sputnik — have been throwing fuel on the fire, tweeting out provocative messages by the hundreds over the past week; every time the government shuts down a voting app, Assange tweets a link to a new one.

The wave of Catalan nationalism that has erupted this year has been building for a long time — centuries, in fact. The regional government has said that if the vote passes, it is prepared to declare Catalonia’s independence within 48 hours. The Spanish government in Madrid, headed by Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, has declared the referendum illegal and unconstitutional — and is committed to stopping it. “The vote,” Rajoy vows, “will never take place.”

Regional unrest is not new to Spain. The Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (or ETA, the acronym for Basque Homeland and Liberty), the militant arm of the Basque separatist movement in Spain’s north, has fought for independence with terror bombings that have killed hundreds. But the Catalan situation is unprecedented, in part because of its support from outside the country. Assange and Snowden are widely suspected of fronting for Russia, which as part of its campaign to destabilize Western democracies has supported secessionist movements from Scotland to Texas. Barcelona and the surrounding resort towns along the Costa Brava are favorite vacation and second-home spots for wealthy Russians, including alleged Mafia heads reportedly linked to the Kremlin. Some of them are facing criminal charges by the national government — charges that might not survive a transition to a new, Russia-friendly Catalan national government. “The situation is confusing and highly combustible,” says one longtime resident who declined to be quoted by name, given the intensity of feeling on the issue.

Appearing before the Catalan government building in Barcelona’s main square, Carles Puigdemont, president of Catalonia, denounced the arrests. “The [national] government has crossed a red line separating it from totalitarian regimes and has become a democratic shame.” The autonomous government of Catalonia, he added, had effectively been shut down that morning by Madrid.

Catalonia, which has its own distinctive culture and language, was never fully assimilated into Spain, itself a patchwork of 17 autonomous regions. But the primary grievance now is economic. Comprising 16 percent of the country’s population, the region contributes more than 19 percent of Spain’s GDP, and while it enjoys substantial autonomy, Catalans often complain that they don’t get enough in return.

Events have played out at a dizzying pace. The act establishing the referendum was rammed through the Catalan Parliament just two weeks ago, during a tense 11-hour session that prompted 52 members of the three opposition parties to walk out, lamenting that the Parliament had been hijacked by separatists. The only question on the ballot will be: “Do you want Catalonia to be an independent country in the form of a republic?” A second law passed that night declared that regardless of how many voters participate, if the yes votes win on Oct. 1, a new independent country will be formed within two days.

The latest polls show that only 41 percent of Catalans favor independence, with nearly 49 percent against it. But anyone following the issue on the WikiLeaks Twitter account might imagine that tanks are rolling down the streets of Barcelona, civil war has broken out, a “Spanish Tiananmen Square” may be imminent — and the late dictator Francisco Franco has returned from the grave to crush Catalonia’s aspirations. On Sept. 11 — National Catalonia Day — when a million demonstrators filled the streets waving Catalan flags and calling for independence, Assange tweeted, “If today is a guide, on Oct. 1 Europe will birth a new 7.5m nation or civil war.”

“Catalonia will decide its own future on October 1,” declared Catalan President Puigdemont. “No one has the authority or the power to seize our right to decide.”

The government in Madrid loudly disagreed: Rajoy lambasted the move as “an intolerable act of disobedience,” and the Constitutional Court in Madrid promptly suspended both Catalan laws. Last Friday, Rajoy thundered into Barcelona, threatening to dissolve the considerable autonomy that the region already enjoys. He backed the threat by taking over the Catalan government finances, including payrolls for the local police — a maneuver that some here believe will make it impossible to hold the referendum.

But Puigdemont and the separatist faction of the Catalan government have vowed to carry on, and in recent days the game of cat and mouse has escalated. Puigdemont called upon the 948 mayors across Catalonia to make preparations to hold the vote; Rajoy warned that they’d be criminally prosecuted, though that didn’t stop the 700-plus officials who heeded Puigdemont’s request to ready the voting booths from rallying in Barcelona on Saturday, promising, “We will vote!”

Puigdemont — who faces criminal charges of disobedience, abuse of power and misusing public funds — called upon citizens to pressure the remaining mayors to join the movement. Some have reportedly received death threats. The Catalan government sent out letters to 55,000 voters across the region, commanding them to staff the voting booths; Rajoy’s government ordered the national postal service not to deliver the letters, then raided private courier services who’d taken over delivery. The national government shut down Catalan sites promoting the vote and independence; the Catalan government put them up again via proxies — a clever move publicized by Assange and Russia’s English-language news outlet RT.

In dozens of tweets, Assange dramatically kept up the drumbeat, recounting the raids on pro-secession newspapers and the plants suspected of printing ballots and posters and the confiscated ballot boxes. He didn’t care about independence, Assange tweeted, but he supported Catalonia’s right to decide — apparently even if it went against the Constitution.

The specifics for a vision of a free and independent Catalonia are vague. Financial advisers have warned that secession would ruin the regional economy, and the move would automatically mean cutting ties to the European Union. Catalonia would have to reapply to the EU, a process that typically takes years. Banks and corporations have threatened to move elsewhere. Catalonia’s Moody’s bond rating puts it on a par with Bangladesh, and nobody seems quite sure what currency Catalonia would use.

Despite the uncertainties and the constant cries of illegality from Madrid, Puigdemont and the Catalan Parliament, where separatists hold a narrow majority, have stoked the concept for months.

They’ve traveled to countries from Denmark to Morocco, without much to show for it. Several weeks ago they hired lobbyists — paying the U.S. firm SGR $60,000 to press the secession cause on Capitol Hill. Their biggest success was with Rep. Dana Rohrabacher, R-Calif., referred to by some as “Putin’s favorite congressman,” who recently met with Assange in his London Embassy hideout. Rohrabacher has said he supports self-determination for Catalonia, though that doesn’t reflect official U.S. policy. Given that Spain is a close ally of the U.S. and a member of NATO, the Catalan separatist cause has achieved little traction in the international community.

On Sept. 20, Barcelona awoke to news that the finance ministry had been seized, with at least 12 high-ranking officials and consultants arrested — reportedly accused of diverting public funds to support the referendum. Even though it was later revealed that the order hadn’t come from Rajoy, who was reportedly unaware until the news broke, he quickly became the object of Catalan anger.

“Spain’s government acts like a banana monarchy — embarrassing for Europe!” Assange tweeted, and also stirred the pot by asking if Rajoy should resign and warning Catalans that Madrid might cut all internet access — a claim that appears to be without basis.

Within two hours, thousands of locals gathered in front of the uptown ministry, waving flags, singing the Catalan anthem, and chanting “Democracy!” “We will vote!” and “Out with the occupation forces!” — reminiscent of the 1970s chants in the protests against Franco’s rule.

A block away, on Passeig de Gràcia, life went on as normal. Shoppers walked by clutching bags from clothing store Zara, and Japanese tourists lined up in front of buildings whose façades display the fantastical swirls and swoops of architect Antoni Gaudí.

“The separatists are just orchestrating a theater here, looking for international outrage,” says a resident who grew up in Barcelona and is against secession. “Nothing will change here.” And he supports Rajoy’s actions. “Madrid is simply applying the rule of law — like any other country would.”

Given Spain’s constitutional prohibition on unilateral secession — specifically its requirement that all Spaniards vote on the matter if one region wants to secede — Rajoy appears legally in the right. He’s backed by the king, the Spanish government, and even his main opposition in the Spanish Parliament — the Socialists — as well as some anti-secession Catalan politicians. He has the authority to declare an emergency and deploy troops, moves that he’s promised to avoid. The police have allowed demonstrations to take place unimpeded. While some liken Rajoy to Turkey’s autocratic President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, others liken him to President Abraham Lincoln, desperately striving to preserve the union.

But some citizens are bothered by the spectacle of a national government squelching a region’s right to self-determination. A recent El Pais poll showed that a majority of Catalans believed that while the current referendum appears to be illegal, Madrid’s actions are only tipping the balance for the separatists. “When you have the government raiding printing offices, confiscating information about a vote, it looks oppressive,” says one local investment broker.

And back in London, Julian Assange continues his Free Catalonia marathon, tapping out more than 80 provocative tweets in recent days, using archival photos showing police in riot gear (which currently they aren’t wearing) dragging off a protester and tanks (which currently aren’t in use here). His dramatic updates have led to media speculation that Assange is actually fronting for Russia, a charge he denies.

But Russia’s interest in Catalonia is clear. The Russian news agency RT has been assiduously covering the Catalan crisis. Catalonia sent a delegate for the last two years to a forum in Moscow run by a Kremlin-supported organization, the Anti-Globalization Movement of Russia. The delegate, José Enrique Folch, promised that if Catalonia became independent, it would accept Russia’s annexation of Crimea and drop sanctions against Moscow. The only international politicians who have taken up the Catalan cause appear to be Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and Venezuela’s dictatorial President Nicolás Maduro, both of whom are close to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

When contacted yesterday, Folch, who works outside Barcelona as an international economist, and whose party isn’t in the Parliament, was equivocal about Catalonia’s future foreign policy, saying that its stance on Crimea and sanctions would depend on whether Russia recognized an independent Catalonia. He remained hopeful that Catalonia would stage its referendum on Oct. 1 and become a free republic two days later. The actions of Madrid were “absolutely criminal, absolutely unacceptable,” he said. Then he lowered his voice and said, “We’re being persecuted.” It was a good thing I’d called when I did, he added: “We’re not sure how long we can talk about the matter freely.”

Melissa Rossi, a writer based in Barcelona, is the author of the geopolitical series “What Every American Should Know” (Plume/Penguin).