Inside Nollywood, the booming film industry that makes 1,500 movies a year

In 1992, after years of watching only imported American, Indian or Chinese films, Nigeria’s local film industry had its first real hit. “Living in Bondage,” a straight-to-video dramatic thriller, followed a man who sacrificed his wife to a satanic cult and afterwards was haunted by her ghost. Many mark the film as the unofficial start of Nigeria’s home-grown film industry, dubbed “Nollywood,” which produces an incredible 1,500 or more movies a year — vastly more than Hollywood, and second in number only to India’s film industry, Bollywood.

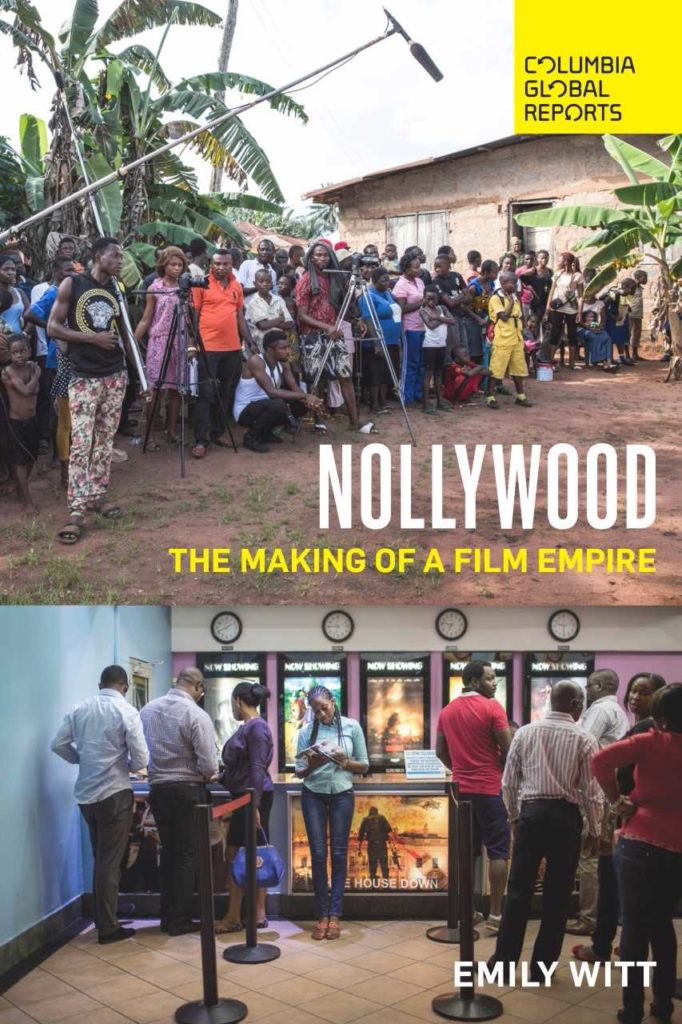

Today, Nollywood films are available globally on cellphones, Netflix and YouTube, and on streets across Africa. In her new book “Nollywood: The Making of a Film Empire,” journalist Emily Witt argues that Nollywood is positioned to become a global brand much like the films of Bollywood or kung fu movies. This despite the many obstacles filmmakers might face: electricity cuts, fuel scarcity, political instability and more.

The book’s introduction, as relayed to Witt by Nigerian documentary filmmaker Femi Odugbemi, describes how cinema and other culture in Nigeria was dominated for decades by the narratives of the colonialists. (Nigeria was under British rule from 1901 to 1960, when an independence movement led to self-government.) But then, Odugbemi told Witt, “People who were the consumers began to become the storytellers… There were a lot of films in Nigeria through the years, but none spoke our voice. None recognized our existence as a distinct culture, as a distinct civilization, a distinct aspiration. ”

For the first time, movies in Nigeria showed not “poverty porn” about the country, Odugbemi said, but also that there were people who had eight cars and big houses. It showed people faithful to their wives and people who cheated, just as happened in the West. And it fixated on some of the country’s particular interests, in mythology, in spirituality, in the environment.

Just a decade after “Living in Bondage,” Nollywood films, made in some 300 languages, were being watched in both urban and rural areas, distributed on both the streets and online, and finding their way into international festivals. And since the 2000s, Nollywood films have only continue to proliferate and spread. We recently spoke to Witt about the cultural phenomenon, how it’s spread, and how Nollywood films today are both distinctively Nigerian and globally influenced.

“Nollywood: The Making of a Film Empire,” by Emily Witt. Published by Columbia Global Reports

ELIZABETH FLOCK: Why did you want to write about Nollywood?

EMILY WITT: Columbia Global Reports asked me to do it, but I had done a Fulbright in Mozambique, and had written about cinema there. I had encountered Nollywood movies for sale. I watched a few of the movies, and they were unlike anything I had seen before. There were elements of a soap opera but they were much crazier than that, the production values were often very poor, and yet they were very popular.

ELIZABETH FLOCK: Nollywood is now the world’s second largest film industry in terms of number of films produced. How did this happen, and in such a short period of time?

EMILY WITT: The industry came out of an extremely difficult time in Nigeria where all the movie theaters closed, state television networks couldn’t pay anybody and the currency had tanked so they couldn’t import movies anymore. Out of that they started shooting movies on VHS and copying and distributing them on the street because the hunger for local entertainment was so strong.

There’s also a strong tradition of theater and storytelling in Nigeria — it’s a literary powerhouse. And there’s something unique about Nigeria in the sense that it has a really strong sense of cultural pride. Nigerians just like Nigerian stuff better than from other places. It’s true for the fashion, the music, the language, as compared to other countries in Africa. Nigerians also saw an opportunity to create content that has black people in it, instead of [those colonialist narratives].

A Nollywood DVD cover. Courtesy of Columbia Global Reports

ELIZABETH FLOCK: Nollywood movies are now available on Netflix and elsewhere online. Who’s watching?

EMILY WITT: It’s still mostly diasporic audiences, somebody who’s emigrated from Nigeria, who will watch a movie on Netflix. These new digital platforms have allowed Nollywood to be more available. Before if you were abroad and trying to watch a Nollywood movie, a mom-and-pop shop would take out a movie from a pile at random, and the packaging was pretty bootleg. Now these movies that were outside of formal distribution are finding their way into them. But there hasn’t been a big crossover hit yet.

ELIZABETH FLOCK: Can you talk a bit more about what makes Nollywood movies distinctive? And how their stories or look is changing?

EMILY WITT: What I came to understand when I was there is that there are two classes of movies that reflect the hierarchy in Nigeria. Since cinemas have reopened, a number of movies are made by wealthier or middle class Nigerians, some of them educated abroad. But the industry’s roots are really in the marketplace and in ordinary people, some of whom were trained at Nigeria’s state television station. Now, there’s a generation of people making more cinematic movies of higher production value. There are urban stories, that are more cosmopolitan, and with less moralism than old Nollywood movies. But I spoke to some actors who had a foot in both the old Nollywood, churning them out by the dozens, and in the more cinematic industry. What gets them recognition on the street from the bus driver or market lady or street vendor, though, is the old Nollywood movies they’d made.

And older-style production values have improved a lot. But they tend to favor traditional stories often with a strong moral message. They might be slightly formulaic, like a fairy tale often has certain tropes. The king is dressed as a beggar, for example, trying to find a wife for his son. That kind of almost folkloric story gets told 10 different ways in 10 different stories, versus a new Nollywood movie that is a little more glitz and glamour.

ELIZABETH FLOCK: Can you talk about a specific Nollywood movie you loved?

EMILY WITT: There’s a horror movie called “Ojuju” by a young director named C.J. Obasi, and it’s an homage to George Romero’s “Night of the Living Dead.” It’s a zombie movie but what carries the virus is untreated water that people in Lagos [the country’s capital and biggest city] are drinking. So there’s a bit of social commentary about the lack of access to clean water in Nigeria. And it’s the zombie trope but with the figure of a juju, which is the Nigerian version of the zombie. It’s about a group of friends, and there’s a last woman standing who makes it out, so it also follows horror tropes. What I liked about it is it has cultural specific instances and social messages but also follows this global movie format. And I think that’s one of the reasons Nollywood has been able to transcend boundaries around Africa.

ELIZABETH FLOCK: Is there a way to tell just how popular Nollywood movies are? Or what the most popular movie is?

EMILY WITT: Well it’s hard to measure, because most of it is sold on the street. But you see the films everywhere, even really far away from West Africa, in Ghana and Kenya. It’s really word of mouth, especially movies made in Eastern Nigeria. People will go to see something with a familiar face, like actress Mercy Johnson, and they don’t even care what the movie is. It depends on the kind of movie you want to watch. There is the dynastic village movie where people wear traditional costume, there is the the tale of a family feud, there are religious movies…

What’s the most popular title? One reporter I spoke to told me it was “Nkoli Nwa Nsukka” because when he went to the funeral of the director’s father it was really lavish. And it had like 15 sequels. He said that’s the way I can tell.

ELIZABETH FLOCK: What can Nollywood tell us about the national psyche? What it can reveal about Nigeria today?

EMILY WITT: You can learn a lot. For one, that Nigeria is a country with a strong moral consensus: about what family looks like, what your sexuality looks like, what it means to be a man or a woman and what’s asked of you. You can learn a lot about how the country sees what a good person is. You can also learn a lot because it’s a country with extremes of wealth and poverty, and people are always making and losing these fortunes in the movies — it says a lot about the instability with which people live, and the lack of practical opportunities to advance. When people get rich, it’s sometimes misbegotten or feels like a windfall from a miracle.

One thing I always found a little amusing while watching the movies is that people would have jobs, or be seen giving a presentation, but the jobs are never really identified — just a businessman showing an upward moving line graph. There’s a couple exceptions, but a lot of times the jobs are vague. So the economic anxiety comes through in the films, just as the religiosity comes through, or the views about children.

ELIZABETH FLOCK: And Hollywood and Bollywood, the world’s two other biggest film industries — are those films being watched in Nigeria too?

EMILY WITT: Bollywood is popular in the Hausa community [a community in Northern Nigeria, who are mostly Muslim]. Nigerian producers are also talking about a future “Slumdog Millionaire” moment, when a Nollywood movie would make a crossover the way a Bollywood movie did. It’s not a bad example, because if it were to happen I think it would be a bicultural production.

Hollywood is everywhere. What I found interesting, but not surprising at all, is what you usually saw for sale, or even on a movie or on TV, is — I’ve never seen so much Danny Glover as sitting in bars in Nigeria. Hollywood has ignored black people for so long, and so the movies that get shown in Nigeria, that people buy, they have black actors. The pirated stuff I saw there was “Empire,” “Scandal,” or a show with Viola Davis. And “Game of Thrones” too, but definitely more movies with African American actors.

–

Source: PBS