By Abayomi TJ Ishola.

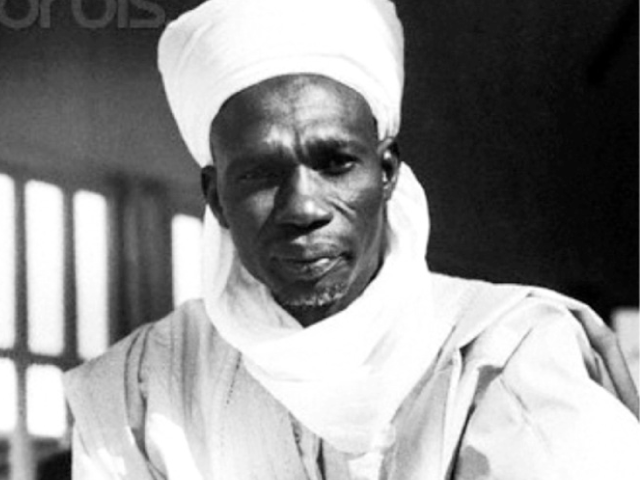

The miseducation of Northern Nigeria did not begin in classrooms, nor did it originate in religion or culture. It began when governance lost accountability and leadership lost memory. It began when vision was assassinated alongside the men who embodied it. To understand the North’s educational, political, and developmental crisis today, one must return to January 1966, when Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto, and Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa were killed. Their deaths were not merely political tragedies; they were ideological executions. What died with them was a coherent philosophy of leadership as stewardship, development as planning, and education as the moral and administrative spine of society. What replaced it was power without consequence and authority without responsibility.

At independence in 1960, Northern Nigeria did not lack leaders. What it possessed, rare even now, was structured continuity. Leadership was understood as a relay, not a scramble. Under Sir Ahmadu Bello, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Hassan Usman Katsina, Sir Kashim Ibrahim, Chief Sunday Awoniyi, Joseph Tarka, Aminu Kano and others, governance was anchored on moral authority, regional cohesion, education, and productive economics. This was not nostalgia or accidental idealism; it was institutionalised policy. The Northern leadership understood that mass education without economic planning would produce frustration, not progress, and that power without accountability would rot from within.

Institutions were therefore built deliberately as public instruments, not personal estates. Ahmadu Bello University, established in 1962, was designed to produce administrators, engineers, teachers, scientists, and technocrats for Northern development. The Northern Nigeria Development Corporation was funded largely by proceeds from cotton, groundnuts, hides and skins exports, financing industrial estates, textile mills such as Kaduna Textiles and Arewa Textiles, scholarship schemes, and human capital pipelines. Regional marketing boards stabilised farmer incomes and ensured that agriculture financed education and industry. Graduates were absorbed into public service. Housing schemes, employment guarantees, and welfare provisions were not populist gestures but outcomes of a planned, production-based regional economy. Education, governance, and productivity were bound together by accountability.

The 1966 coup shattered this equilibrium. With the assassination of Sir Ahmadu Bello and Sir Tafawa Balewa, Northern Nigeria lost not only leaders but continuity of purpose. Military rule that followed centralised power while decentralising responsibility. Regional economic autonomy was dismantled. Long-term planning gave way to decrees and improvisation. Mentorship was replaced by command loyalty. Governance became transactional rather than developmental. Education budgets became expendable because no one feared the electorate. When classrooms collapsed, no governor answered. When teachers went unpaid, no minister resigned. When millions of children were excluded from formal education, the state shrugged. Miseducation took root not as ignorance, but as betrayal.

As accountability evaporated, the state retreated from its responsibilities. Public schools decayed. Teacher training weakened. Education lost its organic link to employment, productivity, and civic responsibility. Into this vacuum stepped unregulated religious schooling, particularly a distorted Almajiri system that had once been structured but now became mass neglect. This was not a failure of faith; it was a failure of governance. The final blow came in the late 1980s with Structural Adjustment and the abolition of marketing boards. Northern Nigeria’s production-based economy collapsed. Agriculture value chains died. Textile manufacturing withered. Vocational education became irrelevant. Politics shifted from production to rent-seeking, from building regional capacity to chasing federal allocations. Survival politics replaced developmental politics.

Yet the Northern story is not uniformly bleak. Kano State stands as an instructive, if incomplete, counter-example. Over successive administrations, Kano invested deliberately in school renovations, rehabilitation of primary and secondary infrastructure, and the establishment of two state universities, expanding access to tertiary education. The state also pursued overseas scholarship schemes, sending brilliant Northerners abroad in science, medicine, engineering, and technology with the explicit aim of rebuilding human capital. These interventions demonstrate an important truth: progress is possible within the Nigerian federation when education is treated as strategy rather than slogan.

However, Kano also exposes the deeper Northern crisis: lack of cohesion. These policies were not replicated systematically across other Northern states. There is no harmonised regional education framework, no shared benchmarks for school quality, teacher training, or tertiary expansion, and no coordinated scholarship-to-employment pipeline across the North. Educational progress remains state-specific, episodic, and personality-driven. The result is uneven development: islands of reform in a sea of neglect. Without regional coordination, even well-intentioned policies struggle to scale or endure.

This absence of cohesion mirrors the broader political failure of the North in the post–First Republic era. The North continues to produce powerful individuals but not a collective agenda. The profound miscalculation with Muhammadu Buhari illustrates this failure of strategic thinking. From 2003 to 2015, Northern elites rallied behind Buhari as a symbol of integrity and discipline. He was marketed as a moral corrective, not a system builder. When he finally won in 2015, no leadership school emerged, no mentorship pipeline was institutionalised, no coherent Northern development agenda was articulated. Buhari’s personal moral standing did not translate into institutional reform. Once again, leadership was reduced to personality rather than continuity.

Northern Nigeria still possesses experienced leaders with depth and competence: Atiku Abubakar with unmatched private-sector exposure and understanding of fiscal federalism; Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso with sustained investment in education and human capital; Senator Jonah David Jang as a symbol of minority participation and identity navigation; Kashim Shettima with crisis governance experience from Borno; General Theophilus Danjuma representing moral courage and principled leadership; Nasir El-Rufai with infrastructure reform credentials; Yakubu Dogara symbolising constitutionalism and inclusion; Aminu Tambuwal with legislative and executive depth; Ahmad Lawan with budgeting experience; Bukola Saraki with institutional reform capacity; Aliyu Wamakko with grassroots mobilisation; and Babagana Zulum with security-informed humanitarian governance. The problem is not the absence of leaders but leadership without ideology and coordination. Competence without cohesion fragments.

Atiku Abubakar’s role in this failure deserves particular scrutiny. His relentless focus on the presidency, on ruling Nigeria, has paradoxically limited his relevance to Northern development. In pursuing national power, he has overlooked other pathways to enduring influence: convening a Northern development coalition, championing a binding regional education compact, or leading a non-partisan effort to harmonise policies on schooling, skills, and economic revival across Northern states. Statesmanship is not exhausted by electoral ambition. The North does not primarily need another presidential bid; it needs an architect of cohesion. Atiku’s experience positions him for this role, but ambition has so far eclipsed opportunity.

Today, Northern Nigeria bears the heaviest burden of neglect despite producing the bulk of Nigeria’s political leadership. Capital projects decay. Rail and road networks crumble. Schools remain underfunded. Security is overstretched. Poverty indices are disproportionately high. Federal allocations meant for education, infrastructure, and security are mismanaged by elites who themselves benefited from free education, scholarships, and social justice structures of the old North. Elders no longer mentor. Institutions no longer transmit values. Young people are mobilised as political foot soldiers, not prepared as future leaders.

More dangerously, the North has failed to interrogate worst-case scenarios. If Nigeria fractures under economic pressure, insecurity, or ethnic fragmentation, what becomes of a region already weighed down by poverty, porous borders, arms proliferation, and food insecurity? Survival thinking demands preparation for rupture, not blind faith in continuity.

What went wrong was not destiny. It was the destruction of production-based economics, the collapse of mentorship, and the abandonment of accountability. The North traded agriculture value chains, manufacturing, and vocational education for rent-seeking politics. Leadership became episodic, not generational. Memory died, and vision followed.

The way forward is neither sentimental nor optional. Northern Nigeria must return to first principles: human capital development anchored in quality education and skills; security sector reform rooted in local intelligence and community trust; regional economic revival through agro-processing, solid minerals, and manufacturing; leadership mentorship and succession institutions; moral reorientation that restores civic responsibility; and deliberate intergenerational leadership pipelines. Crucially, successful state-level examples like Kano must be regionalised, standardised, and scaled through a Northern policy compact that survives personalities.

Unity is not a slogan; it is existential. 2027 is not about ambition; it is about survival. For elites, it is a final chance to correct history. For the poor, it is a fight for dignity. For the youth, it is a moment of becoming. Titles must lose their power. Ego must retreat. The North must sit together again, not as lords dividing spoils, but as stewards rebuilding a broken house.

History has already shown what the North once built. The present exposes what neglect has destroyed. The future will ask only one question: whether this generation had the courage to replace ambition with cohesion and restore accountability and continuity or whether it allowed the house to collapse completely while arguing over who should rule the ruins.