BY BLAISE UDUNZE

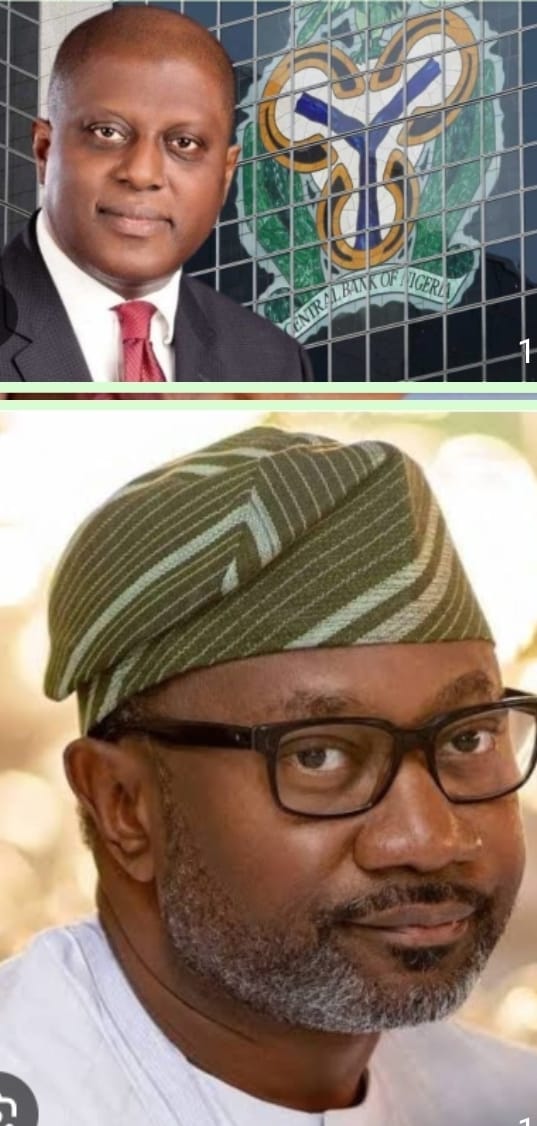

The Olayemi Cardoso-led Central Bank of Nigeria’s 24-month compliance timeline for the recapitalization of Nigeria’s banking system is about to conclude on March 31, 2026, which is framed as an unavoidable solution to systemic fragility, weak balance sheets, and the demands of a larger, more complex economy. Bigger capital, regulators argue, will produce stronger banks. Though First Bank may have met the CBN’s N500 billion minimum requirement, the latest financials from Femi Otedola-led First HoldCo Plc, which is the parent of Nigeria’s oldest commercial bank, offer a sobering counterpoint, revealing that capital alone cannot cure structural weakness, governance failure, or deep-rooted risk management flaws. If capital is the answer, what exactly is the problem?

What is truly astonishing to many is that beneath the headline growth in earnings lies a financial institution struggling with collapsing earnings quality, surging credit impairments, volatile fair-value exposures, and rising operating inefficiencies. First HoldCo’s numbers are not merely a company-specific disappointment; they are a mirror reflecting the deeper fault lines within Nigeria’s financial system and a warning that recapitalisation, in its current form, risks becoming another cosmetic reset rather than a genuine reform.

On the surface, the topline appears encouraging. The figures showed that gross earnings rose by 17.1 percent to N2.64 trillion in the nine months to 2025, while interest income surged by over 40 percent to N2.29 trillion. Figuring it out, investors, depositors, and analysts understand that these figures, however, are largely the product of a high-interest-rate environment driven by aggressive monetary tightening. They reflect repricing, not necessarily improved lending quality or superior balance-sheet strength. In an economy under strain, rising interest income often signals the transfer of macroeconomic stress from borrowers to banks, rather than sustainable growth.

This becomes evident once attention shifts from revenues to profitability. The performance disclosed that profit before tax declined by 7.3 percent to N566.5 billion, while profit after tax fell nearly 13 percent to N458 billion. Earnings per share dropped by a steep 27.7 percent, a sharper decline than headline profit suggests, pointing to dilution pressures and reduced value accruing to shareholders. More striking still is the full-year picture, where profit after tax from continuing operations collapsed by about 92 percent, plunging to N52.7 billion from N663.5 billion in the prior year. Such a dramatic fall cannot be explained by temporary volatility; it is the consequence of long-suppressed risks finally surfacing.

The most damaging of these risks is asset quality. The most critical figure is the impairment charges that rose by nearly 69 percent in the nine months to N288.9 billion, and by over 75 percent on a full-year basis to N748 billion, and invariably, these numbers tell a story of borrowers buckling under FX exposure, weak cash flows, and a deteriorating operating environment. They also raise uncomfortable questions about credit underwriting standards, concentration risk, and the effectiveness of internal risk controls in earlier lending cycles. After impairments, much of the benefit from higher interest income evaporated, exposing the fragility of earnings built on stressed credit.

Compounding this weakness was a sharp reversal in fair-value accounting. First HoldCo recorded a net loss of N87 billion on financial instruments measured at fair value, a stark contrast to the N549 billion gain recorded a year earlier. Due to this outcome, larger chunks of shareholders’ value were wiped out because this single swing accounted for a negative variance of over N636 billion year-on-year.

The episode highlights a dangerous dependence on market revaluations and FX-driven gains to prop up earnings, as seen that the moment conditions turn, paper profits vanish just as quickly, raising questions about the transparency, sustainability and economic substance of reported results.

Non-interest income provided little cushion. In the nine months to 2025, it declined by 44.5 percent, falling from N618.7 billion to N343.7 billion. While net fees and commission income rose by about 25 percent, the increase was too small to offset the collapse in other income lines. The result is a revenue base that is narrow, volatile, and overly exposed to market swings. Recapitalising banks without addressing this lack of income diversification simply amplifies vulnerability.

At the same time, operating costs surged. Operating expenses climbed by nearly 40 percent to N942.7 billion, while other operating expenses jumped over 43 percent on a full-year basis. Inflation, FX depreciation, energy costs, and technology spending all played a role, but the deeper issue is efficiency. Costs are rising far faster than sustainable income, eroding margins and weakening internal capital generation at precisely the moment banks are being asked to shore up capital buffers. Injecting fresh capital into institutions with broken cost structures does not resolve inefficiency; it merely postpones the inevitable days.

These financial stresses revive longstanding concerns about governance and risk culture in Nigeria’s banking system. Large impairment charges and valuation reversals do not emerge overnight. They accumulate through years of weak credit governance, excessive sector and obligor concentration, insider-related exposures, inadequate stress testing, and regulatory forbearance. Recapitalisation does not answer the most important questions: who gets credit, how risks are approved, how boards exercise oversight, and whether management is truly accountable. Without reform in these areas, more capital simply provides a thicker cushion for future losses.

Foreign exchange risk remains the system’s most dangerous and least resolved fault line. Currency devaluation inflates asset values and boosts interest income on paper, while simultaneously crushing borrowers with FX-denominated obligations. Banks may book translation or revaluation gains even as credit quality deteriorates beneath the surface. This contradiction fuels earnings volatility and undermines confidence in financial reporting. A stronger capital base does not neutralise FX mismatch risk; only disciplined risk management, credible macro policy, and transparent reporting can.

Perhaps most troubling is what First HoldCo’s results imply about regulatory credibility. Many of the impairments and valuation losses reflect risks that were visible long before they crystallised in the income statement. When losses arrive suddenly and in clusters, concerns from different quarters are raised and markets begin to question whether supervision is proactive or merely reactive. Recapitalisation without restoring trust in regulatory oversight risks being interpreted as an admission that deeper problems remain unaddressed and by extension, this erodes trust in the system and a stronger banking sector must also be a fairer and more accountable one.

Nigeria has travelled this road before. Bigger banks and higher capital thresholds have previously delivered reassuring headlines, only for familiar weaknesses to resurface in new forms. First HoldCo’s numbers demonstrate that capital adequacy, while necessary, is far from sufficient. Without the CBN confronting governance failures, asset quality deterioration, concentration risk, FX exposure, transparency gaps, and weak risk culture, recapitalisation risks will become another exercise in delay rather than reform.

The uncomfortable truth is that real stability requires more than fresh equity. It demands honest loss recognition, credible financial reporting, disciplined credit practices, diversified income streams, and regulators willing to enforce standards consistently. Until these missing pieces are addressed, recapitalisation will remain what it too often has been in Nigeria’s financial history, as a larger buffer for the same old problems, and a temporary comfort masking unresolved fragilities.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos, can be reached via: blaise.udunze@gmail.com