…exposes how foreign firms’ tax evasion playbook bleeds Nigeria’s airport revenue dry

By Dooyum Naadzenga

An FG concessionaire tasked with revenue generation through above-the-line advertising concessions contracted Excel-LED—a Chinese LED manufacturer also operating as Exel LED, Exel LED Optoelectronics, and Adsen—expecting reliable delivery of airport-grade screens. Instead, the deal unraveled into a multi-million naira scam at Enugu, Abuja, and Port Harcourt airports.

Documented evidence reveals foreign firms and Nigerian intermediaries diverting project payments from corporate to personal accounts, dodging taxes and starving the Federal Government of vital revenue.

P

The Deal That Turned Sour:

At the heart of the scandal: stalled LED installations at three key airports, particularly Port Harcourt, where a verified multi-million naira transfer went to a personal account, following a pattern of early failures masked as successes and total non-delivery.

These screens were meant to generate non-aeronautical revenue through advertising and flight displays—critical funds for terminal upgrades and reducing aviation sector debt.The concessionaire performed due diligence, confirming Excel-LED’s manufacturing credentials and its representative “Sam Lee” as capable of high-traffic systems. Initial payments went to the company’s verified corporate account in China.

The first three screens arrived on time but failed technical evaluation—one plagued by a persistent issue that sidelined it for six months in Enugu, costing the company and FG millions in lost revenue. After much pleading from Excel-LED representative promising “Redemption,” the concessionaire gave them another chance, building false trust despite the red flags.

Open link below

The scam pivoted in the final phase for Enugu, Abuja, and Port Harcourt. Nigerian fixer “Ndubuisi” introduced Emmanuel Shoon Patrick as Excel-LED’s local representative for logistics, fabrication, and installation. Payments were redirected from Excel-LED’s China account to Patrick’s personal Nigerian bank account, justified as needed for customs clearance, on-ground costs, and faster transfers.

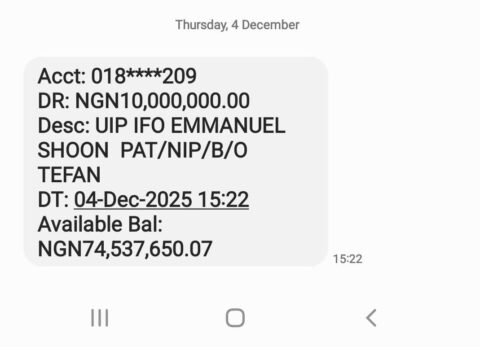

On December 4, 2025, at 15:22, the concessionaire authorized a major transfer from its project account (ending in 209). Bank records confirm the debit “in favour of” Emmanuel Shoon Patrick.Shoon assured immediate installations, promising completion right after the first tranche—following the standard sequence of advance payment, delivery, installation, testing, balance payment, and handover.

This had appeared to work in prior jobs at Owerri, Enugu, and Calabar, despite the initial failures. But Shoon, posing as CEO of Excel-LED Nigeria Limited, pocketed the advance and fled to China. No delivery. No refund. Revenue losses mounted for the FG and concessionaire, with per-minute delays in advertising income. Contacts to the Chinese firm went silent or were forwarded to Shoon—clear evidence of collusion and obtaining money under false pretences.As of this report, site logs and project documents show zero deliveries post-redirection. Installation teams ghosted multiple dates. Excuses cited Chinese production bottlenecks, shipping woes, and logistics—but no proof emerged. Procurement records, expense breakdowns, and timelines went unanswered.

Communications with Ndubuisi and Patrick dried up. The screens remain dark, with the diverted funds unlinked to Excel-LED’s corporate books.

Tax Evasion Patterns in Infrastructure Deals:

Experts in cross-border projects note that corporate payments trigger FIRS withholding tax, VAT, and filings. Personal accounts evade this via fake “consultancy fees” or “facilitation payments.” Nigeria hemorrhages billions yearly from such leaks in LED displays, telecom, data centers, and power projects.

The playbook:

Foreign vendors nail initial deals via official channels for credibility, then insert local intermediaries. Big payments shift to personal accounts as “urgent costs.” Deliveries stall amid vague excuses.Excel-LED’s alias proliferation fits this hit-and-run model.Cascading Losses to Revenue and InfrastructureThe fallout is brutal.

The concessionaire eats costs for site prep and lost ad deals. FG concession terms mandate sharing non-aeronautical revenue; dead screens wipe out slots at high-traffic hubs, costing tens to hundreds of millions monthly. In mature airports, this revenue hits 30-50% of income—starving self-funding. It also chills investors, stalling Nigeria’s airport digitization and smart-city push.

The Recurring Playbook and Next Steps:

Stakeholders confirm the script: Early deliveries (flawed or not) via corporate channels. Mid-project, new “facilitators” handle customs and deployment. Funds reroute to personal accounts. Deliveries halt with production/shipping alibis. Blame-shifting follows across borders.The concessionaire is assembling a dossier—contracts, emails with Sam Lee and Redemption, chats with Ndubuisi and Patrick, bank proofs, and non-delivery reports—for law enforcement, anti-corruption bodies, FIRS tax probes, and aviation regulators. All parties will get a chance to respond.

Red flags abound: Mid-project intermediaries sans track record, personal-account redirects, scope vagueness, milestone resistance, and ignored technical failures. These expose Nigeria’s digital infrastructure vulnerabilities in airports, energy, signage, and telecom.